[ad_1]

What do Victor Wembanyama and Connor Bedard have in common with Diana Taurasi, John Elway and Bryce Harper? The No. 1 overall picks in this summer’s NBA and NHL drafts are considered can’t-miss, generational prospects in their respective sports, just like Taurasi, Elway and Harper were in their times. They’re some of the best and most celebrated prospects … ever.

That got us thinking. Where would Wembanyama and Bedard stack up all-time in their sports based on pre-draft hype? We decided to create brackets matching the talented players against each other to find out.

We asked our draft experts and analysts at ESPN to come up with a list of the eight most-hyped prospects in the sports they cover since 1979, when ESPN was founded. We enlisted Kiley McDaniel for MLB, Kevin Pelton for the NBA, Mel Kiper Jr. for the NFL, Greg Wyshynski for the NHL and M.A. Voepel for the WNBA. Kiper has pre-draft scouting reports for football prospects going back 40-plus years, while our other experts got help from people inside the leagues they cover to go back that far.

To create each bracket, we matched up each sport’s prospects based on their draft years, seeding them oldest vs. most recent. We then picked winners in each round, creating semifinals and a final for all five sports. Remember, this is based on pre-draft hype and talent, not what happened after the draft. Some of the prospects below became Hall of Famers, of course, but others struggled to live up to their potential.

Let’s get started with …

Jump to a sport:

MLB | NBA | NFL | NHL | WNBA

Who’s next? Here are the big names for 2024 and beyond

McDaniel’s most-hyped MLB prospects bracket

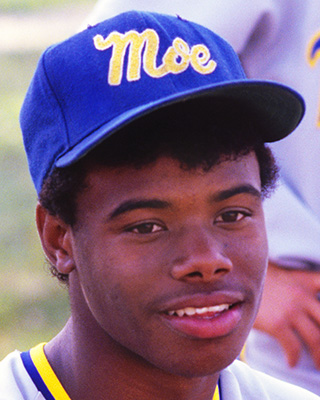

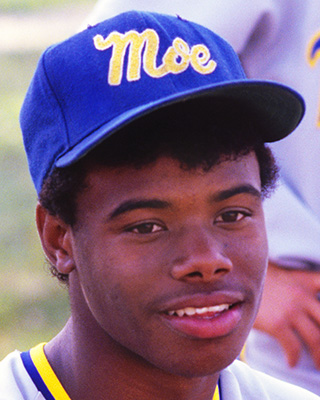

The son of a three-time major league All-Star, Griffey Jr. grew up in MLB clubhouses and was immediately recognizable when the Seattle Mariners made him the No. 1 overall pick in the 1987 draft out of Cincinnati’s Moeller High School.

Griffey was more than just a famous name at the time he was drafted, of course, receiving future grades of 7 for hitting, 8 for power, 6 for speed, 6 for arm strength and 7 for range on the Mariners’ pre-draft scouting report. While some of Griffey’s hype exploded in his meteoric rise to the majors after being drafted — see: 1989 Upper Deck card and every young baseball fan in the U.S. suddenly turning their hats backward — those grades help underscore that the hype began before he came off the draft board to Seattle.

A native of Portland, Oregon, Rutschman actually grew up attending Mariners games in the Pacific Northwest — though Rutschman was just 12 years old when Griffey played his last major league game in 2010.

The switch-hitting catcher built himself into a No. 1 overall pick by putting up sensational numbers at Oregon State — hitting over .400 in each of his final two seasons with the Beavers, winning a College World Series Most Outstanding Player award and drawing comparisons to Buster Posey — before going to the Baltimore Orioles in 2019.

Winner: Griffey. He gets the nod for avoiding the stigma and risk that come with catching prospects, but more so for having the coveted combination of obvious up-the-middle tools, easy actions and polished skills along with big league bloodlines.

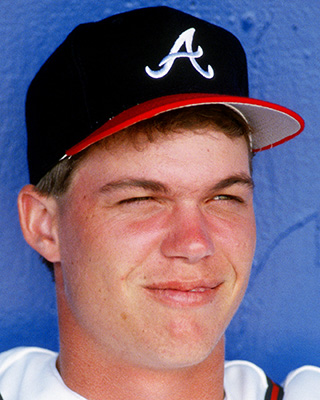

Jones might lag behind the other players on this list when it comes to hype — after all, any collector of ’90s baseball cards will tell you that Todd Van Poppel was the name to know in the 1990 draft class — but he more than made up for that with his ability.

How good was Jones as a Florida high school prospect? Well, he went 11-1 with a 0.81 ERA and 107 strikeouts in 84 innings during his best prep season on the mound and was named first-team all-state as a wide receiver — and yet there was never a question that switch-hitting in the major leagues would be his ultimate career path.

There has simply never been a more hyped prospect at the time they were drafted than Harper was coming out of Las Vegas. As a 16-year-old, he graced the cover of Sports Illustrated next to a bold font headline calling him “Baseball’s Chosen One” followed by a subhead declaring him “the most exciting prodigy since LeBron.”

Within that story, Harper was compared to not only baseball’s Justin Upton, Alex Rodriguez and Griffey but also LeBron James, Tiger Woods and Wayne Gretzky. And his play on the field backed up all the hype. Long before he was the No. 1 overall pick in the 2010 draft, Harper’s 500-foot home runs were already the stuff of legend and he fast-tracked his way to that draft by playing college baseball at the College of Southern Nevada — as a 17-year-old. All he did was hit .443 with 31 home runs and a .987 slugging percentage, winning college baseball’s most prestigious award — the Golden Spikes Award — while playing at a junior college.

Winner: Harper. This is the closest matchup in the first round for me and it may be a combination of recency and hype bias, but I had been hearing about Harper and how he was a generational slam dunk 1/1 pick since early in his high school career. He would’ve been a real catching prospect if he wasn’t such an advanced hitter that he demolished JC pitching as a 17-year-old with a wood bat.

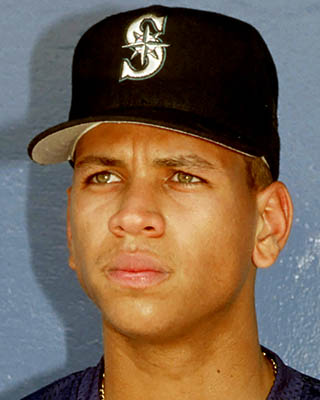

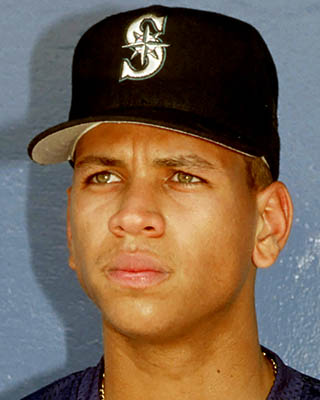

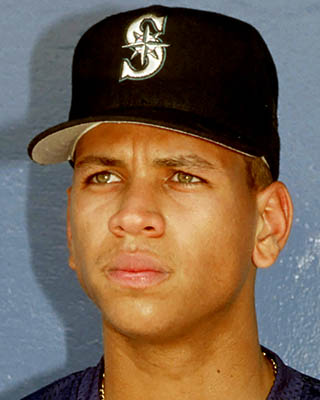

Had Rodriguez’s high school career come just a decade or two later, the hype that would have spread about his game via social media and the internet probably would have rivaled Bryce Harper’s or even LeBron James’. But when it comes to pure talent as a draft prospect, Rodriguez is second to none.

In a time when big shortstops were still a rarity in baseball, Rodriguez had scouts flocking to Miami to see “The Next Cal Ripken” dominate at Westminster High School. The trouble with the comparison to a multiple-time MVP and Hall of Famer like Ripken is it actually might have been a little light for the five-tool player that A-Rod had already developed into at the time.

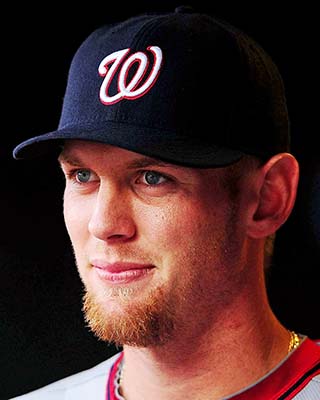

Strasburg is the only pitcher to make this list, and since we’re looking at both talent and hype at draft time in these rankings, there’s simply nobody else who comes close to where he was in both categories coming out of San Diego State in 2009.

Stras was actually something of a late bloomer for a generational prospect, but once the buzz around his triple-digit heater, plus-plus breaking stuff and ideal ace size got going, there was no stopping it. In fact, Strasburg was so dominant during his time with the Aztecs that it’s hard to believe these numbers from his final season aren’t a typo: 13-1 record, 1.32 ERA, 0.77 WHIP and an unimaginable 195 strikeouts in 109 innings. Yes, that’s a 16.1 K/9 rate — five-plus strikeouts per nine innings more than the best ratio in MLB history.

Winner: A-Rod. Strasburg is the best college pitching prospect in my lifetime, but he drew a bad matchup here. He’s not only facing a position player, but one of the most perfect prospects of all time, who was identified as having every tool you could imagine early in the process.

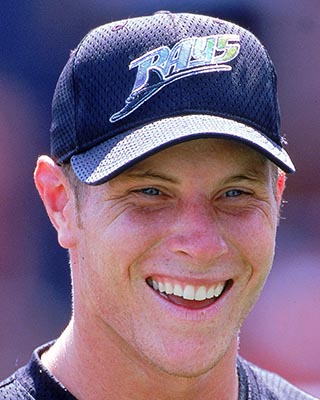

We all know that Hamilton’s path to major league stardom was anything but a straight line — but that shouldn’t take away from the prospect he was as a North Carolina prep star before going No. 1 overall in the 1999 MLB draft.

The first high school outfielder to go No. 1 overall since Griffey Jr., Hamilton also hit 96 mph on the mound as a left-handed hitter, but when scouts went to Raleigh to see him, they left talking about a position player who could do it all — with legendary power. Hamilton hit .529 with 13 home runs, 35 RBIs and 20 steals in 25 games. He finished his career at Athens Drive High School near the top of any conversation about the best amateur baseball player anywhere.

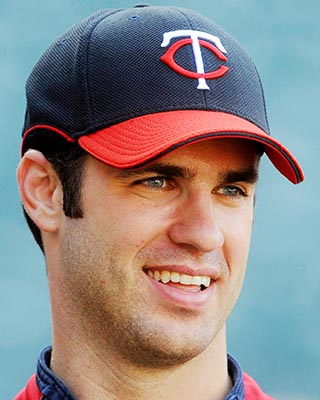

All you need to know about Mauer as a three-sport high school star can be summed up in one statistic that sounds more like folklore than reality: He struck out one time in his entire high school career.

Mauer was also named National Player of the Year in both baseball and football, committed to play quarterback at Florida State before going No. 1 overall in the 2001 MLB draft, hit .605 with 15 home runs as a senior and averaged 20 points per game as an All-State basketball player. It’s safe to say that if this was an overall sports résumé at the time of being drafted, Mauer would be a pretty heavy favorite to come out of the baseball bracket. Oh, and he did all of this playing at a premium defensive position that simply has not seen players with Mauer’s all-around package of tools very often.

Winner: Hamilton. If you think about the draft prospect who was the most overwhelming to scout with the soundtrack to “Field of Dreams” playing in the background of his game as everyone watched slack-jawed, it was Josh Hamilton. He was the best many scouts had seen at literally everything on a baseball field: a five-tool talent who dabbled in the upper-90s on the mound from the left side in high school back when that barely existed in the big leagues.

The winner: Hamilton. Griffey may seem like the perfect draft prospect for the reasons above, but many scouts still rave that Hamilton is the best amateur player they’ve ever seen, and this is based on a pre-draft evaluation. Hamilton gets the slight edge here.

The winner: A-Rod. Harper may be the most hyped prospect in draft history — and he came with both age and competition-level edges over A-Rod — but the ideal prospect a scout could draw up is basically just a vague description of A-Rod’s scouting report at any time in his career.

The winner: A-Rod. This is, as you’d expect, the closest matchup of this whole process. We have the Platonic ideal of a baseball prospect in A-Rod vs. probably the overall most talented teenage baseball player in my lifetime in Hamilton. The edge here goes to A-Rod because all of his talent was packed into what he became in the big leagues while Hamilton’s exploits on the mound were a fun thing to watch and talk about but ultimately never impacted his prospect status, just the legend.

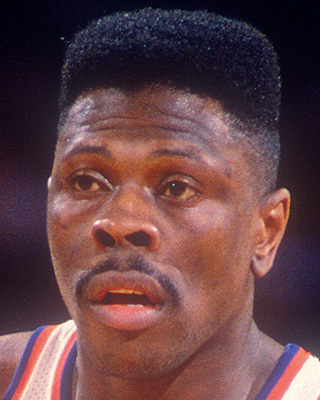

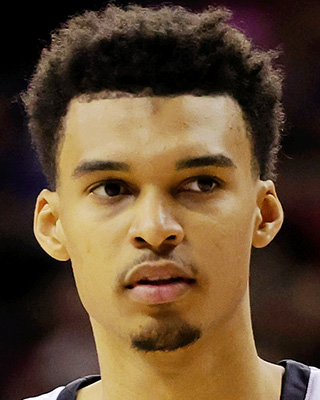

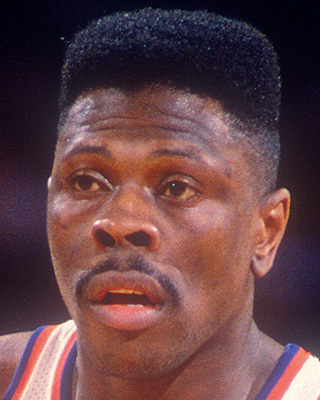

Pelton’s most-hyped NBA prospects bracket

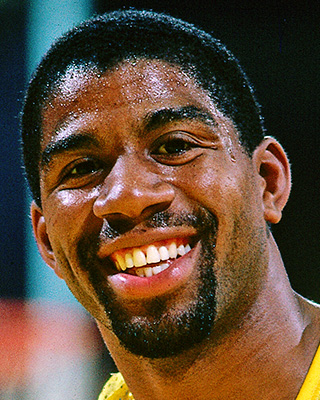

Our first matchup contrasts a No. 1 pick fresh off playing in the most-watched college basketball game of all time (Johnson’s Michigan State Spartans beating Larry Bird‘s Indiana State Sycamores for the national championship) and one who played just twice in the U.S. before being drafted.

The winner: Wembanyama. Despite the excitement about Johnson, there still were questions about the viability of a 6-foot-9 point guard. Jerry West, then a scout for the Lakers before becoming GM, famously preferred Sidney Moncrief to Johnson with the No. 1 pick. There was never any doubt Wembanyama would go No. 1 overall.

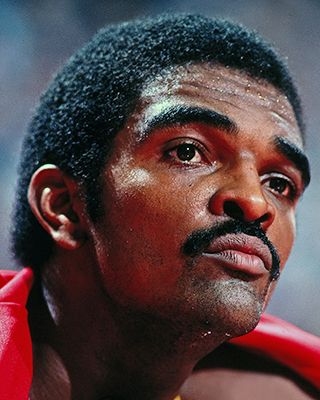

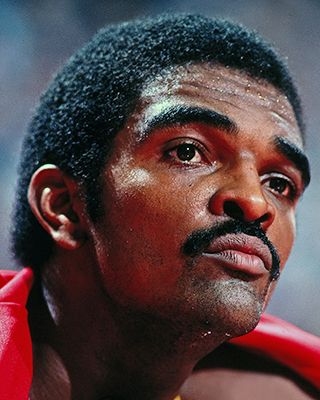

Ralph Sampson (1983) vs. Anthony Davis (2012)

Given Sampson’s career was hampered by injuries after he won All-Star MVP and made All-NBA second team in 1985, it’s easy to forget his towering presence as a prospect. Sampson won the Wooden Award three times, matching Bill Walton for most ever, albeit not as a freshman like Davis did in his lone season at Kentucky when he also led the young Wildcats to the title.

The winner: Sampson. In October 1983, The New York Times compared his arrival in the NBA to the four greatest prospects prior to our timeline: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Wilt Chamberlain, Bill Russell and Walton.

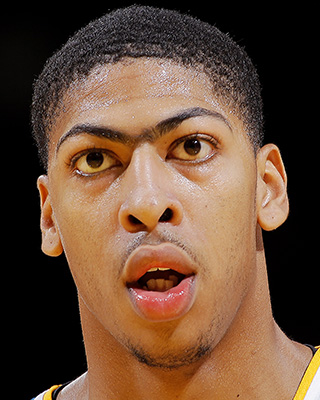

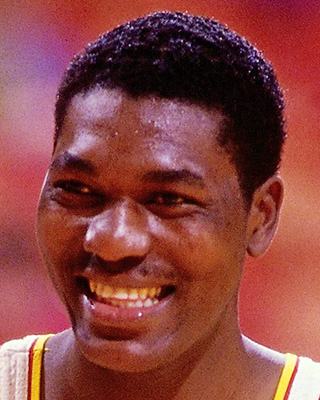

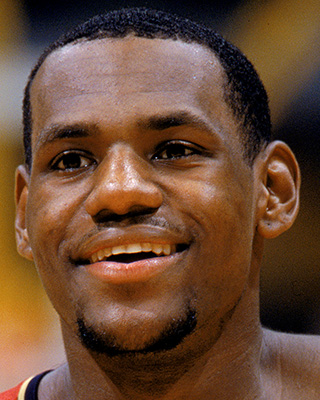

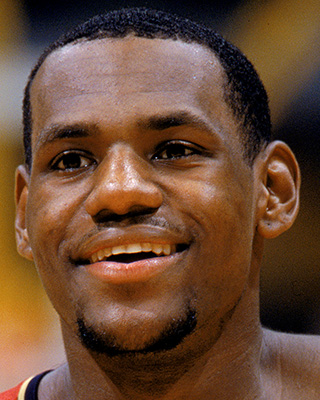

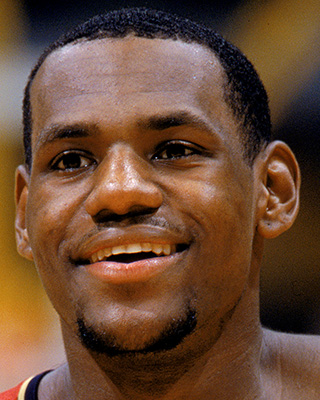

It’s testament to how incredible Olajuwon was as a prospect that the Rockets are never second-guessed for taking him No. 1 over Michael Jordan. Olajuwon had led the Houston Cougars to a championship as Most Outstanding Player of the 1983 Final Four. The hype around James out of St. Vincent-St. Mary High School included a Sports Illustrated cover and ESPN broadcasting his games before that became commonplace.

The winner: James. He entered the league at age 18 with the expectation of becoming the league’s best player, which can’t be said about Olajuwon — rated behind contemporaries Sampson and Patrick Ewing.

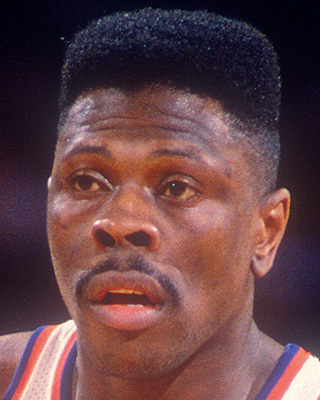

This could easily be the final. Both of these franchise centers inspired teams to plan around the draft. In Ewing’s case, the NBA installed the first-ever draft lottery, which conveniently sent him to the New York Knicks. Despite the lottery, seven teams won 26 games or fewer during Duncan’s senior season, still tied for the most ever in a full season.

The winner: Ewing. We’re splitting hairs here, but Ewing’s Georgetown Hoyas went to three title games and won one. Duncan’s Wake Forest Demon Deacons didn’t enjoy that level of success, a small knock against him.

The winner: Ewing. Given the different eras, it’s challenging to compare the excitement around Ewing as a prospect in the early days of cable TV to Wembanyama at a time of far greater interest in the draft and projecting what players can be. Still, in a scenario where Ewing and Wembanyama were in the same draft class with their pre-NBA accomplishments, I suspect teams would consider Ewing the surer bet based on his long track record of college dominance.

The winner: James. As much as Sampson impressed at Virginia, there were questions too. Why had the Cavaliers fallen short of the Final Four his last two seasons? Virginia was upset in 1982 by UAB in the Sweet 16 and the Elite Eight by eventual national champion North Carolina State in 1983. In James’ case, the only qualms were about whether the attention was too much, too soon. His game was closer to a lock.

The winner: Ewing. To some degree, this is surely unfair to James. Had he played in an era where he spent four years at Ohio State or another college, developing the same way he did with the Cleveland Cavaliers — James was an All-NBA first team pick by his third NBA season — there would be little doubt he tops the list.

Because James had only gone up against other high schoolers, there was still a mild undercurrent of skepticism about his NBA superstardom that did not exist for Ewing, making the latter the best prospect since 1979.

Kiper’s most-hyped NFL prospects bracket

Did you know only one defensive back has been picked No. 1 overall in the NFL draft? And it wasn’t Lott, whom I graded as a 9.9 prospect in 1981, the first year I made my annual “Blue Book” available to the public. (My scale went to 10, but I never gave out a perfect score.) It was Gary Glick, a safety out of Colorado A&M who went to the Steelers in 1956. I say this because Lott actually went eighth in his class, though two of the defenders above him made the Hall of Fame (Lawrence Taylor and Kenny Easley, my second-ranked defensive back in 1981).

It’s funny to say now, but teams just didn’t value cornerbacks as much as they do now, simply because the NFL back then was built around running the ball and stopping the run. Lott could do it all, though. He was an outstanding cornerback at USC, picking off eight passes as a senior. I thought he’d make the move to safety (he eventually did in 1985), writing in my scouting report that he “has everything it takes to be the best pure safety” in the league. Still, teams knew they would get a star in Lott, and there was hype around his potential as a rookie. For me, he was the clear top prospect on the board, no matter where he ended up. Another line from my scouting report: “An outstanding player who doesn’t seem to have a weakness.” Lott had 61 picks over a stellar 14-year career for the 49ers, Raiders and Jets.

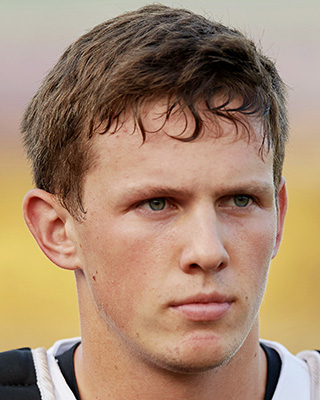

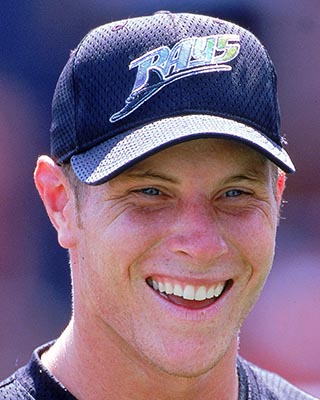

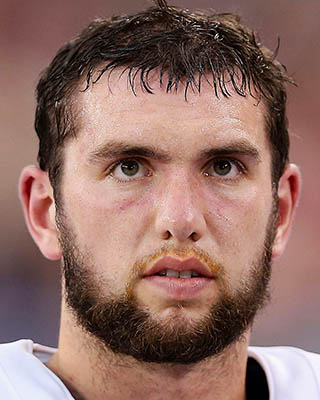

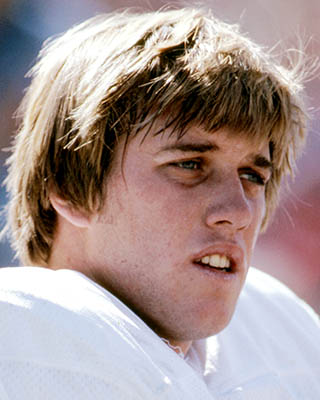

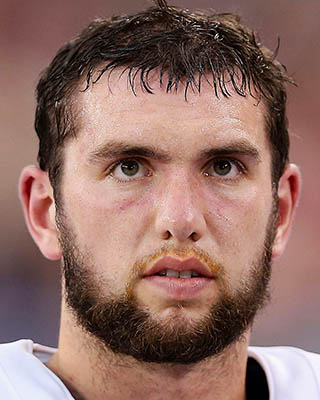

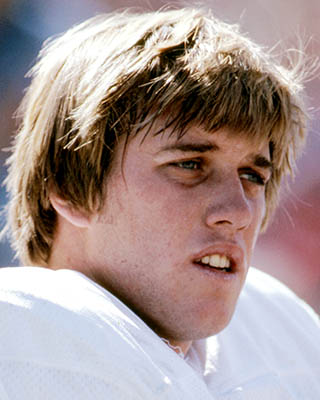

The college hype around Luck, the youngest player on my list and one of two quarterbacks, was so enormous that he likely would have been the No. 1 pick in the 2011 draft (over Cam Newton) if he hadn’t returned to Stanford. All he did in his final collegiate season was throw 37 touchdown passes with 10 picks while completing 71.3% of his attempts, finishing No. 2 in the Heisman Trophy voting (for the second straight year). There was public debate about whether Luck or Robert Griffin III — who beat out Luck for the 2011 Heisman — should go No. 1 overall to the Colts, but there wasn’t much private discussion among scouts and execs in the league; Luck was considered to be on a different level.

It says a lot about Luck’s talent then that the Colts moved on from one of the best quarterbacks of all time to take him. Peyton Manning had missed the 2011 season and was recovering from fusion surgery on his neck, with Indianapolis going 2-14 without its star. That led the franchise to Luck, who was the total package. “Arm strength, size, smarts, demeanor — it’s all there,” is what I wrote at the time. His career didn’t quite go how we thought, but he was a tremendous player and surefire Hall of Famer if he had played a few more years.

The winner: Luck. He was the wire-to-wire pick as the top prospect in his class, supplanting one of the greatest players in league history and not missing a beat. No offense to Lott, but this one isn’t close.

Elway needs no introduction, right? I’ve had my fair share of misses in my years of evaluating prospects, but Elway lived up to the hype of his Stanford film. Here’s what I wrote in my final scouting report before the 1983 draft: “Without question Elway is a can’t-miss All-Pro NFL QB who has the ability to make a place for himself in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.”

That’s exactly what he did, winning two Super Bowl titles to finish his career before being a first-ballot Hall of Famer in 2004. I gave Elway a 9.9 grade, my highest ever for a quarterback (tied with Andrew Luck). That 1983 draft lives on as one of the best first rounds ever — there were seven HOFers in the first 28 picks, including Jim Kelly and Dan Marino — but Elway stands above them all.

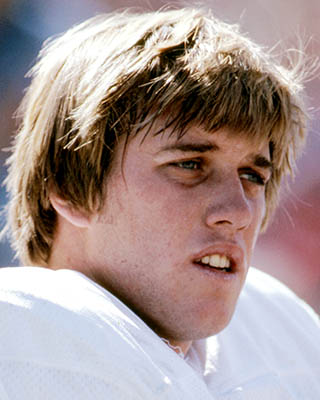

The 2007 draft will be most remembered for JaMarcus Russell‘s remarkable rise and fall as the Raiders’ pick at No. 1 overall, but it was the future Hall of Famer Johnson who was my top-ranked prospect in the class. What he did at the combine at 6-foot-5, 239 pounds — running a 4.35-second 40-yard dash — had never been done before. He combined an unbelievable workout with production (1,202 receiving yards, 15 touchdowns in his final season at Georgia Tech). I gave Johnson a 9.8 grade, my highest ever for a wideout, and he ended up with the Lions at No. 2 overall.

Johnson was seen before the draft as an instant NFL star the minute he stepped foot on the field, though in reality he had some growing pains, including being the go-to playmaker on Detroit’s infamous 0-16 team in 2008. Still, he more than lived up to his hype, despite playing just nine seasons.

The winner: Elway. He was the best prospect in a legendary draft class, with some of the best quarterback traits I’ve ever studied. Johnson was supremely talented, too, but it’s tougher to project receivers because so much of their pro output depends on which team drafts them.

The defensive linemen on this list get paired against each other here. They are two of the three 9.9 grades I’ve ever given to front-seven players (the other was linebacker Hugh Green in 1981). Smith was seen as an unmissable pass-rusher coming out of Virginia Tech, where he racked up 38 sacks in his final two seasons. At 6-foot-3, 278 pounds, he was just as good against the run, despite often being triple-teamed at the snap. In my slightly dramatic pre-draft scouting report, I called Smith a “ferocious man-eater” and compared him to future Hall of Famer Lee Roy Selmon.

Simply put, Smith was a no-brainer No. 1 pick — and he was taken there in two different drafts (NFL and USFL). Smith, of course, went on to have a legendary career, with 200 sacks across 19 seasons for Buffalo and Washington. He had double-digit sacks in 13 seasons. He was a phenomenal defender who played up to his epic potential.

If you haven’t seen clips of Emtman play in college at Washington, I suggest you seek them out. Here’s what I wrote about him in 2013, when I looked back at some of my highest-graded prospects ever: “To watch Emtman’s college tape during his junior season at Washington was to witness a guy who seemed totally unblockable. It was as if he and the offensive lineman were the magnets of the same pole — the O-lineman just bounced into the backfield. For perspective, Emtman was No. 4 in the Heisman voting — as a defensive tackle.”

The 6-foot-4, 290-pound tackle was a lock to go No. 1 overall to the Colts, who actually had both of the top two picks that year (they took linebacker Quentin Coryatt at No. 2). Emtman struggled with injuries in the NFL and ended up with just five sacks in 18 games over three seasons in Indianapolis. Funnily enough, that was the final NFL draft with 12 rounds … and it produced exactly zero Hall of Famers. Drafting is really hard.

The winner: Smith. It’s easy to say in hindsight that Smith was the clear better player, but if we’re talking about pre-draft evaluations and hype around them, this one is extremely close. Ultimately, it comes down to Smith and his “unparalleled athletic skills,” a note that I included in my pre-draft report. You can’t teach what he had.

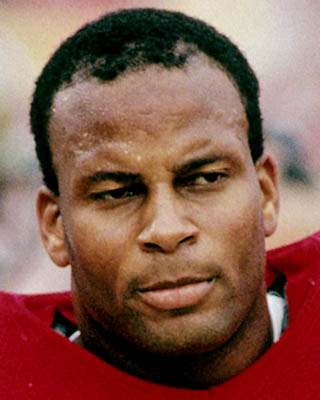

Jackson was a no-brainer as the No. 1 overall pick in the 1986 draft, a 9.9 grade on my board. He had size, speed, toughness and production — he had just won the Heisman Trophy at Auburn after rushing for 1,786 yards and 17 touchdowns. Here’s a line from my pre-draft scouting report: “[Jackson] rates as a better prospect than Eric Dickerson, and could easily go on to break the NFL records held by Walter Payton.” That’s hype.

The problem? No one knew if he’d actually play for the Bucs if they took him with the top pick. He had threatened to turn down a contract and reenter the draft. When I did a mock draft for The Los Angeles Times a few days before Round 1, I projected Jackson to Tampa Bay but wrote “Don’t take trade rumors seriously.” Turns out I was right. Jackson, though, followed through with his threat. He ended up playing professional baseball, then was picked in Round 7 by the Raiders in 1987. Injuries limited Jackson’s NFL career to just four seasons, but he was a fantastic talent.

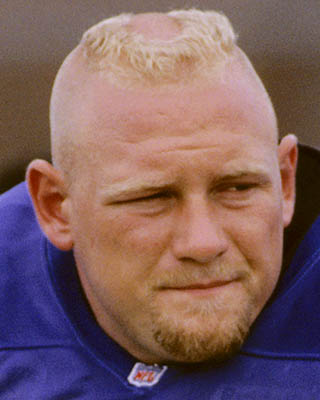

As for Mandarich, he was the first of his kind, a model of what the NFL was about to become. When you see a 6-foot-5, 305-pound offensive tackle run a sub-4.7-second 40-yard dash these days, you don’t bat an eye. Thirty years ago, though, it was unheard of. He wowed NFL teams with his size/speed combo in workouts, but he had stellar tape at Michigan State too. What we didn’t know was how he got those bulging muscles, which contributed to his short career after going No. 2 overall to the Packers.

Mandarich has now become a common example for a draft “bust,” but I’m not a fan of the term. He didn’t live up to his potential, sure, but he did start 63 games in the NFL. There were execs at the time who thought he should go No. 1. It also doesn’t help him that he was the only top-five pick in 1989 who didn’t end up making the Hall of Fame (Troy Aikman, Barry Sanders, Derrick Thomas and Deion Sanders). Mandarich is the only 9.9 grade I gave for an offensive lineman, with Orlando Pace (1997) just behind him.

The winner: Jackson. This is a tough one, because both were considered to be superstars in their own right. Still, Jackson gets the edge because of the position he played and all the touchdowns he scored. He was simply one of the most special talents I’ve ever seen.

The winner: Elway. The two Stanford signal-callers face off, and they could have both been Colts legends. Elway was actually drafted by the Colts (then in Baltimore) and traded to the Broncos after the draft. Elway refused to play for Baltimore. What gives him the edge is that the Colts saw all of the quarterback talent in that draft, knew he had said he wouldn’t play for him and took the risk anyway. They thought he was worth it. One of the lines from my scouting report: “He has no discernible weaknesses and is the prototype QB.”

The winner: Jackson. If we’re talking about hype and what happened leading up to the draft, this is a no-doubter. Jackson was an electrifying dual-threat athlete seen as the archetype of how the NFL would evolve. And remember, the NFL at this time was dominated by lead running backs, and there was a sense that Jackson could make whichever team he chose an instant Super Bowl contender.

The winner: Elway. Two generational players who were also drafted in MLB. The exact same pre-NFL draft grades. And both spurned the team that picked them. Only one can be victorious, though, and I’m giving the edge to Elway. Most people reading this probably don’t remember what it was like before the 1983 draft, but I can assure you he changed the way NFL teams thought about quarterbacks. As I wrote in 2013, Elway’s arm “would stand up to the strongest arms in the current NFL.” He was truly an unbelievable prospect.

Jackson gets dinged a little bit because by the time he actually made it to the NFL — remember, he took a year off to focus on baseball after the Bucs drafted him No. 1 — there were some questions over how he’d fit in a Raiders backfield that already had Marcus Allen.

Wyshynski’s most-hyped NHL prospects bracket

Long before Kobe Bryant switched to No. 24 so he could be, in the words of Kanye West, “one over Jordan,” there was Lemieux wearing No. 66, flipping No. 99 on its head in the same way he hoped to attack Wayne Gretzky‘s throne as the best hockey player in the world.

Super Mario backed up that swagger with a record-setting career with Laval in the QMJHL, scoring 133 goals in 70 games in 1983-84. “Le Magnifique” was one of the first NHL prospects to inspire outright tanking in the NHL, with the Pittsburgh Penguins trading their best defenseman and demoting their best goalie to secure the first overall pick. They’d have no regrets, as Lemieux had a Hall of Fame career, two Stanley Cup wins and would go on to own the franchise.

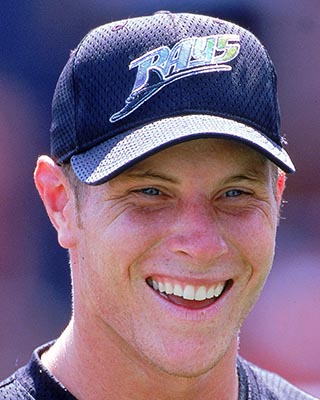

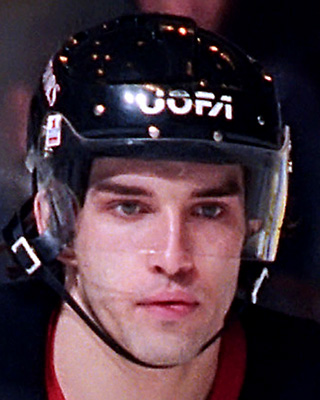

Bedard sat atop a draft class that was considered one of the deepest in recent memory. He earned his franchise player hype thanks to an incredible shot release that earned him 122 goals in 119 games in the WHL, and he dominated the world junior championships like few Canadian prospects had.

Fans willfully got behind “Fail Hard For Bedard” movements for several NHL teams that defied the existence of the draft lottery by positioning themselves for high picks in a loaded draft and a ticket that could win them the next great franchise center, which the Chicago Blackhawks ended up cashing.

The winner: Lemieux. Bedard wasn’t even the best Connor drafted in the past 10 years. Mario was a template-setting generational talent who did things that no one had seen a 6-foot-4 center do before.

The hype for Lindros existed on two levels. There was how he played, with an unprecedented combination of all-world offensive skill and the aggressive brute force of an NFL linebacker. Then there was where he didn’t play: Quebec, which drafted him first overall in 1991 despite Lindros having declared he’d never play for the Nordiques.

One year later, Quebec traded the uber-prospect to both the Philadelphia Flyers and New York Rangers, with an arbitrator determining that the Flyers deal happened first — a five-player, two-draft pick, $15 million-in-cash behemoth that remains one of the biggest blockbusters in sports history.

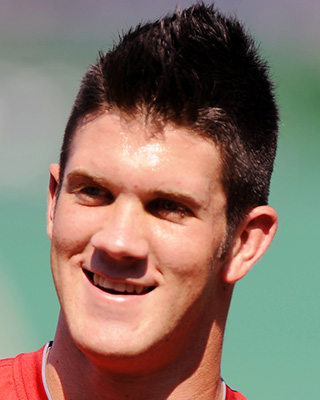

Matthews was advertised as a superstar-in-waiting center with a nontraditional background for the NHL: a Mexican American hockey phenom from Scottsdale, Arizona, who made the unusual decision to play professionally in Switzerland for ZSC Lions the season before he was drafted in 2016.

The Toronto Maple Leafs won the lottery and selected him first overall, with Matthews becoming the first U.S.-born player to go No. 1 since Patrick Kane in 2007.

The winner: Lindros. While Matthews was hyped as a franchise-altering player, Lindros was an obsession. The hype for “Big E” was so immense that he signed a contract with Score sports cards before he was drafted in the NHL, appearing as an Oshawa General with “FUTURE SUPERSTAR” written above him in Score’s 1990-91 set.

That Daigle would become one of the most infamous draft busts in NHL history — despite lasting 10 years in the league — overshadowed the incredible hype that carried him into the 1993 draft. He was a photogenic, bilingual phenom from the Quebec Major Junior League. While both the San Jose Sharks and Ottawa Senators finished with a pathetic .143 points percentage, it was the second-year expansion team Senators who secured the first overall pick and Daigle.

“I’m glad I got drafted first, because no one remembers No. 2,” Daigle said. No. 2 overall in 1993? Hockey Hall of Fame defenseman Chris Pronger. Whoops.

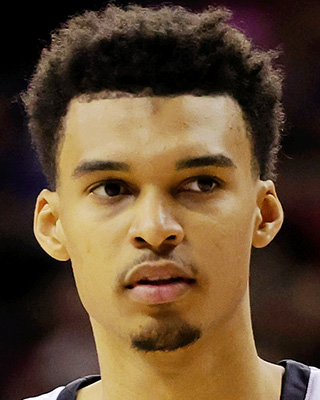

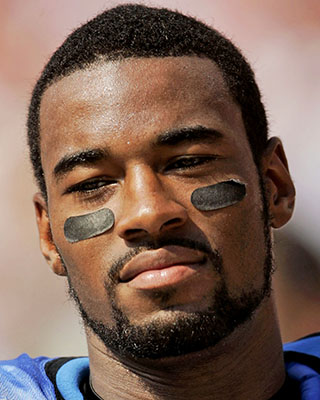

The hype for McDavid started when he was just 14 years old, dazzling scouts in the Greater Toronto Hockey League. He secured exceptional player status from Hockey Canada, entering the junior hockey draft at the age of 15. His legend grew quickly: a center who could make magical offensive plays at an incredible skating velocity. It was, in many ways, an unprecedented skill set.

McDavid was a generational talent and already a human highlight reel. His nickname, uttered without irony from the true believers: “McJesus.”

The winner: McDavid. Teams cleared the decks for a chance to draft him — “Dishonor for Connor” was a cheeky buzz phrase leading up to the 2015 draft. The Edmonton Oilers won the lottery and had their greatest offensive talent since Wayne Gretzky wore the logo.

Ovechkin was already a force of nature at 18 years old, dominating the Russian Super League as a winger for Moscow Dynamo. His skating was as powerful as his shot, his charisma as potent as his offense. The Washington Capitals had undergone a gut renovation in the hopes of securing a new franchise standard-bearer, and that’s what they got in Ovechkin.

Everyone else wanted him, too: Capitals GM George McPhee said no less than 15 teams called him with trade pitches for the top pick in the 2004 draft.

Crosby gave his first media interview at 7 years old. Sid The Kid would give many more on his journey to NHL stardom, as the hockey world anointed him the next generational talent. His future stardom was so palpable that the NHL rewrote its draft rules in 2005. The league cancelled the 2004-05 season due to a lockout. In order to fairly reward a team with the chance to select Crosby, the NHL created a weighted lottery based on playoff appearances in the past three seasons and first overall picks in the past four drafts.

The Pittsburgh Penguins won the “Sidney Crosby Sweepstakes.” He has won them three Stanley Cups so far.

The winner: Crosby. While Ovechkin would win Rookie of the Year, Crosby was on another level when it came to pre-draft expectations.

The winner: Crosby. The hype for both Penguins draft picks was off the charts, but Lemieux didn’t have the benefit of the 2005 media (and internet) landscape.

Plus, not only did the NHL have to rewrite its lottery rules ahead of the Crosby draft, there was actually an entirely different league after the teenaged Sid the Kid: the World Hockey Association, which tried to take on the NHL as a rival league. The WHA offered Crosby a three-year, $7.5 million contract before the 2005 draft. He declined.

The winner: Lindros. The difference between these two heavily hyped phenoms is simple: McDavid was a coveted generational talent whose legend only grew after he entered the NHL, with five scoring titles and three MVP awards, but the apex of Lindros’ fame was as he entered the NHL in soap operatic fashion.

The winner: Crosby. Lindros was a star before he ever played a game in the NHL. His celebrity only grew when he rejected Quebec after being drafted by the Nordiques, fighting the system like he and his family had throughout his years as a mega prospect.

But here’s the thing: The NHL didn’t need Lindros in the early 1990s. It was thriving with Gretzky in Los Angeles and Lemieux, soon to be joined in stardom by Jaromir Jagr, in Pittsburgh. The NHL would have the Rangers‘ Stanley Cup in 1994, an apex moment which might not have happened if New York ended up transacting the Lindros trade — truly one of the NHL’s greatest what-ifs.

The NHL needed Crosby in 2005. Badly. He gave hockey fans something to obsess over during the cancelled season. His future stardom — and make no mistake, he was every bit the hyped can’t-miss player that Lindros was — served as a beacon on the horizon. Not just as a way to get through the dark times of the lockout but as an evocation against the neutral-zone trap that had stifled offensive creativity for a decade. His rivalry with Ovechkin was already established through world junior tournaments. It would help fuel the NHL’s revival after the cancelled season, along with outdoor games and revamped rules.

Lindros was infamous. Crosby was the new hope — for woeful franchises, for the continuation of Canadian hockey glory and for the NHL itself. And for those who were nauseated by that golden boy status, it only added to the loudest buzz that’s ever accompanied an NHL draft prospect.

Voepel’s most-hyped WNBA prospects bracket

“Hyped” means something a bit different in the WNBA, which launched in 1997 and is still growing in its 27th season. The league and its players are still building name recognition. There has been more opportunity for hype in women’s basketball since the advent of social media, which is why just two players in our bracket — Holdsclaw and Diana Taurasi — were drafted in the pre-social media days.

South Carolina‘s A’ja Wilson just missed the list not because of any lack of superstar status — she might win her third WNBA MVP this season — but more due to draft circumstance. Wilson was a surefire pick at No. 1 in 2018 by the Aces, who then were an unknown entity after relocating from San Antonio.

By contrast, Ionescu made the list because of her triple-double prowess — she had an NCAA-record 26 (for men and women) playing for Oregon — and the fact she was going No. 1 to the New York Liberty and the largest media market. Ionescu led the Ducks to the 2019 Final Four, and they were on track to go back in 2020 before the pandemic canceled the NCAA tournament and prematurely ended Ionescu’s college career.

After the Washington Mystics‘ 3-27 debut season in 1998, the franchise’s eyes turned to Holdsclaw. That spring, the 6-foot-2 forward led Tennessee to an undefeated season and their third consecutive NCAA title.

Tennessee missed on a four-peat, upset by Duke in the 1999 Elite Eight, but Holdsclaw finished her Lady Vols career with 3,025 points and 1,295 rebounds, both program records. Even though the 1999 WNBA draft included a large number of veteran pro players who were available because of the demise of the short-lived ABL, Holdsclaw was still the consensus choice at No. 1.

The winner: Ionescu. It came down to the difference in eras. Holdsclaw is one of women’s college basketball’s all-time greats, and she got a lot of attention for the late 1990s. But the spotlight on the sport was bigger two decades later for Ionescu, who also was in the public eye for her friendship with Kobe Bryant and his daughter, Gigi.

Holdsclaw played 11 WNBA seasons, averaging 16.9 points and 7.6 rebounds and being named all-WNBA second team three times and a six-time All-Star. She turned 33 before the end of her final season, which was 2010 in San Antonio.

Ionescu, who has averaged 15.2 PPG, 6.2 RPG and 5.9 APG in her WNBA career, has her detractors who say she gets too much attention. Some complained about her being on the cover of NBA 2K24. Her 3-point contest domination last Saturday was one of the highlights of the recent WNBA All-Star Weekend. At 25, she has a lot of time to win a WNBA title, something the Liberty have never done.

If you want hype, imagine if Delle Donne had stuck with UConn, her first college choice. She would have been a freshman in the fall of 2008, when Moore was a sophomore. Instead, Delle Donne — realizing she wanted to remain close to home for family reasons — left summer workouts at UConn, played volleyball for a season at Delaware and then competed for four seasons there in basketball.

Delaware had never before had a player the caliber of Delle Donne, and likely never will again. But it was a magical time there while it lasted. She had 3,039 points and 1,020 rebounds for the Blue Hens.

Still, the Huskies did just fine led by Moore. She and Tina Charles, the 2010 No. 1 WNBA draft pick, were the stars for UConn’s 90-game winning streak from 2008 to 2010. Moore won two NCAA titles and had two other trips to the Final Four. She finished her UConn career with 3,036 points and 1,276 rebounds.

The winner: Moore. Delle Donne being part of “Three To See” with Brittney Griner and Skylar Diggins-Smith (more on that below) and forging such a different path by opting for Delaware over UConn, had a lot of hype as she joined another No. 2 draft pick, Sylvia Fowles, with the Chicago Sky.

Delle Donne has two WNBA MVP awards to Moore’s one, although she has battled injury issues much more so than the metronomic and reliable Moore. Traded to the Washington Mystics in 2017, Delle Donne won a WNBA championship with them in 2019.

But the draft hype for Moore came both from her high-profile career at UConn and the fact the Minnesota Lynx had assembled a championship-caliber group that was waiting for a dynamic wing player to complete the ensemble. When the Lynx got the 2011 No. 1 pick, they couldn’t have found a better fit than Moore, and vice versa.

In her eight WNBA seasons, Moore led the Lynx to the WNBA Finals six times and won four championships. She stepped away after the 2018 season to focus on social justice work that including helping free from prison the man who would become her husband. Moore made her retirement official earlier this year.

Parker was the rock of the last national championship team for Tennessee, with her back-to-back titles in 2007 and 2008 propelling her into immediate WNBA stardom. She was the No. 1 selection by the Los Angeles Sparks in 2008, the perfect match of big-talent player to big-city market. She won MVP and Rookie of the Year in 2008 — the only player to take both those awards in the same season — as a 6-foot-4 forward/center who could run the point. Parker was a prominent example of a more positionless style of basketball, and she became an inspiration for countless others since who’ve tried to model their game after hers.

The one thing Parker struggled with was winning a WNBA championship, but she got it in 2016. Then in 2021, she signed as a free agent with her hometown Chicago Sky, and won her second WNBA title. This season, at age 37, she’s trying to help the Las Vegas Aces repeat as champions.

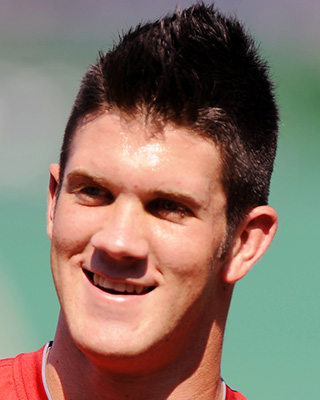

Griner was part of the most hyped draft class in WNBA history. The ESPN marketing campaign for the 2012-13 season focused on these senior standouts: Baylor‘s Griner, Delaware’s Elena Delle Donne and Notre Dame‘s Skylar Diggins-Smith. They were dubbed “Three To See.”

Griner won a national championship in her college career, Diggins-Smith played in three Final Fours and Delle Donne put the mid-major Blue Hens on the map.

A true center who could dunk easily (and still does), Griner led the way in Baylor’s 40-0 national championship season in 2012. She finished with 3,283 points, 1,305 rebounds and an NCAA-record 748 blocked shots.

Part of the hype around Griner wasn’t just that she was a franchise-changing player. The 2012 Mercury went 7-27, and some WNBA followers thought that once their season started to go sour, they intentionally tanked in hopes of landing Griner. The Mercury denied it, but there was even more grumbling when they won the draft lottery.

Griner became a perennial MVP candidate, and has twice won Defensive Player of the Year. The Mercury’s last championship came in her second season in the league, 2014.

The winner: Parker. “Three To See” brought a lot of attention to the 2013 draft, but the hype edge still goes to Parker. Her college career coincided with the early years of the explosion of social media. She was the college game’s biggest star in 2007 and 2008 and played in the last UConn-Tennessee game in which Pat Summitt was still the Lady Vols’ coach. No one knew in 2008 that Summitt was actually so close to the end of her career because of early-onset dementia, Alzheimer’s type. As it turned out, Parker was the last Lady Vol legend to play for Summitt.

The 2008 draft was also during a brief period when the event was held the day after the national championship game in the same city as the Final Four. The hype of the NCAA title carried over immediately to Parker being picked No. 1.

It’s a battle between two UConn legends who came along at different stages of the program, were No. 1 WNBA draft picks and have each won the league’s MVP honor once.

Taurasi won three consecutive NCAA titles for the Huskies. After playing on extremely talented teams her first two seasons, she carried a heavy load in the last two. It prompted UConn coach Geno Auriemma’s famous quip, “We got Diana, and you don’t,” and the cheeky confidence encapsulated the hype surrounding Taurasi as she headed to the WNBA. She has lived up to it.

In 2004, she was selected by the Phoenix Mercury, a franchise that had some early success, advancing to the 1998 WNBA Finals, but between 2001-2006 didn’t make the playoffs. That changed dramatically in 2007, when Phoenix won the first of three WNBA titles. Since, Phoenix has missed the postseason just twice. And Taurasi has been there for all the success.

A five-time Olympian, Taurasi is the WNBA’s all-time leading scorer and is closing in on the 10,000-point mark. At age 41, she continues to start for the Mercury and is under contract through 2024.

Stewart, 28, went one better than Taurasi at UConn: She won four NCAA titles and then was hyped as the key piece to the Seattle Storm renaissance, joining 2015 No. 1 pick Jewell Loyd and veteran Sue Bird in Seattle. It worked exactly as hoped.

The Storm won the 2018 and 2020 league titles with Stewart earning WNBA Finals MVP both times. To date, Stewart has averaged 20.6 points and 8.7 rebounds; a torn Achilles tendon, an injury suffered while playing overseas which sidelining her for the 2019 WNBA season, is the only thing that has slowed her down.

The winner: Taurasi. Her college career was before social media, but she was the focus of a great deal of traditional media. She was part of what’s considered by many as the greatest women’s college team — the 2002 national champions — and then, as mentioned, was the propellant to two more titles. Taurasi also played during the height of the UConn-Tennessee rivalry, which was the biggest story in the women’s game. During her Huskies career, UConn beat Tennessee three times at the Final Four, two of those for the national championship.

The UConn-Tennessee series ended after the 2007 season and didn’t resume until 2020, so Stewart never faced the Lady Vols. Stewart had the rivalry with Notre Dame, and her four NCAA titles made her and fellow 2016 seniors Moriah Jefferson and Morgan Tuck the biggest winners in UConn history. They went 1-2-3 in the 2016 WNBA draft.

Ultimately, Taurasi’s bolder, flashier, love-her-or-hate her personality on court — no UConn player seems more like Auriemma than Taurasi — and being part of the UConn-Tennessee saga give her the hype edge.

The winner: Taurasi. Both guards are native Californians, born 15 years apart, who went elsewhere for college. Taurasi traveled cross-country to join the UConn dynasty, while Ionescu took Oregon to unprecedented heights with the 2019 Final Four. As much as Ionescu’s triple-double success garnered headlines, Taurasi’s four trips to the Final Four and three championships made her an all-time college great who was drafted by Phoenix as a can’t-miss superstar.

The winner: Parker. Both won two NCAA titles and joined pro teams ready to win titles with them. That happened right away for Moore, while it took many years for Parker. For prospect hype, the edge goes to Parker. Her 2008 was epic: NCAA champion, Final Four Most Outstanding Player, No. 1 draft pick, dunked in a WNBA game, Olympic gold medalist, WNBA MVP, WNBA Rookie of the Year. She also found out later that year she was going to have a child; her daughter Lailaa was born in 2009.

The winner: Parker. It’s hard to pick one over the other because both came into the WNBA with the same kind of surefire, future-Hall-of-Famer hype, which turned out to be accurate. And they came from the two most prominent programs in the women’s college game at the time. Taurasi won three NCAA titles to Parker’s two. Taurasi played four years in college to Parker’s three, as Parker redshirted what would have been her first season with a knee injury. Still, Parker could dunk, handle the ball as a post and had the type of game to be a transformational player. The anticipation of Parker joining the WNBA was palpable, especially at a time when the league needed a new infusion of stars.

[ad_2]

Source link